I found myself homebound on the bitterly cold Monday that simultaneously marked a day of honor for Martin Luther King and the second ascendance to the presidency by Donald J. Trump. Not sure what to do with the day, I started where I usually do, over coffee at the kitchen table with our dog Arlo curled up at my feet. As the caffeine awakened my brain, it recognized my heart needed somewhere besides the events of the day to place my focus. Whether it was the movement of the Holy Spirit or the Community Coffee, Howard Thurman came to mind. So, while the world watched what was happening in the Capitol Rotunda, I pulled up the text of his classic work Jesus and the Disinherited.

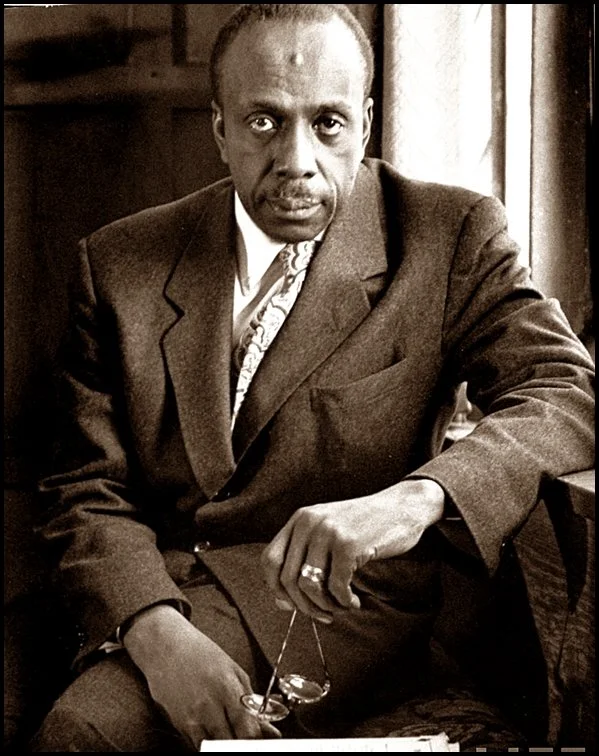

Doctor Thurman was an African American pastor and scholar in the first half of the twentieth century who had a profound influence on the giants of the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. King called him one of his greatest friends and influences. John Lewis, reckoning he would have time to read in jail, placed a copy of Thurman’s masterful work in his backpack on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. He cast a long shadow for a man many have never heard of.

In Jesus and the Disinherited Rev. Thurman weaved together thoughts and themes that we would later recognize in the words of prophets and peacemakers to come. He elevated the power of love over hatred and argued that Jesus’ life exemplified how love can win the battle over the destructive effects of hate. He called out the use of fear as a weapon to control and subjugate people and how Jesus, through God’s powerful love, challenged this abusive tactic.

Thurman also reminded us that Jesus was part of a marginalized group, allowing for a deeper understanding of his teachings by looking through that lens. From the depths of his deep faith and friendships with both Gandhi and Dr. King, he called for non-violent resistance against the oppressive use of power. It is important to note that he wrote all this in 1949. The impact of his thought and influence cannot be overstated.

But one part of this book has touched me most personally. When asked how he could remain a Christian, and loving, and hopeful, he pointed to his maternal grandmother. Nancy Ambrose had lived much of her life as a slave on The McGehee Plantation in Madison County, Florida. Unable to read or write, Miss Nancy helped raise Howard, who as a child would read the Bible to her. However, she discouraged him from reading from Paul, remembering how the “slaver preachers” would use certain texts of his to justify slavery and used the Bible to keep them under subjection.

But she also remembered the influence of “the slave preachers.” In a later in life interview Dr. Thurman shared this intimate account.

“I don’t remember how often this happened, but that it happened at all was tremendously important. And then my sister and I would be very still, because we knew what she was going to tell us – this. Anyway, I can see her getting ready. Then she would say: “he would stand up, start very quietly and then look around to all of us in the room and then he would say “You are not slaves, you are not n*****s, you are God’s children.” And you know, when my grandmother said that she would unconsciously straighten up, head high and chest out, and a faraway look would come on her face.”

“Now”, Thurman said, “that transmitted an idiom to me. And there was nothing in my environment that could touch this. It gave me my identity.”

He also told stories of how Miss Nancy habitually extended kindness towards those who had been consistently unkind to her. Her acts, born of spiritual strength and resolve, insured that hate would not get the last word. Hard as it was, she showed her grandson that he could be kind to folks he disagreed with and who bore him harm. That might help explain his personal affection for Jesus, who against all human inclination, did the same.

I told you earlier that this part of this story has a personal side. Here it is. Like Howard Thurman’s grandmother, I am from Madison County, Florida. I played baseball and music in the local high school and college. As a teenager I picked tobacco and tossed hay on farms that were once plantations. And while often told about the World War II hero, and later the six NFL players and World Series champion from Madison, nobody ever mentioned Nancy Ambrose. Somehow the fact that the greatest influence on the greatest influence on Martin Luther King, Jr. was one of our own was kept a secret. All these years later, I’m hoping word gets out.

So, on this day, I give thanks for Miss Nancy and her grandbaby boy. Thankful for a lady who, against all odds and inclinations, lived a life of love and power, and watched God multiply it a million times over. Thankful for an illiterate, enslaved woman who could still see, know, and feel when religion and scripture were being used as faithless means to unholy ends. And still insist on responding in love.